MOST people would say that ‘Three Colours White’ pales in

comparison to ‘Blue’; that it isn’t as moving, or intense, or meaningful, or as

important in some way. Well that would be to miss the point entirely. It has

completely different aims, even though many of the films’ production team is

the same for both. ‘White’ is a black comedy. The plot is ridiculous at times

and it is very plot-driven, unlike the first film which has many moments of

contemplation, in which the film seems to stand still. The two key male leads

are the same, I believe, as the two leads in another Kieslowski ‘comedy’, from

‘Dekalog’- from memory it is the last or one of the last of the ten one hour

films, about two brothers who inherit their father’s stamp collection with

tragi-comic results. It is because of this association with the earlier film,

that ‘White’ seems even more farcical to me than it possibly is supposed to.

The male lead, in particular, has an amusing face, and is very hard to take seriously.

Kieslowski uses him, in both films, as someone the audience can pity and laugh

at, as much as if to say ‘I’m glad it’s happening to him, and not to me!’

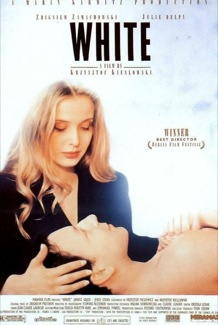

The female lead is Julie Delpy (Dominique) who auditioned

for ‘The Double Life of Veronique’ but would have been terrible, and rejected,

mercifully, the offer to play Julie in ‘Blue.’ In ‘White’ she is good. A bit

like a cat, she is cruel, and sneaky, and cunning, but, when trapped at the

end, we witness her human side and find her more likeable as a result.

Zbigniew Zamachowski’s character (Karol) is signposted as

tragic and ridiculous from the very start. He is visiting the law courts to

find out that his wife, Dominique, wants a divorce because he is inept in the

bedroom. As he is ascending the steps, he looks at a pigeon in the sky.

Suddenly there is a splash of white on his coat, from the pigeon, just as he is

admiring its flight. This is the first sign of his helplessness. This is

Kieslowski marking him as a ridiculous figure who seems destined for bad luck.

He has that sense of resignation all over his face. Soon enough, Karol is seen

pathetically running after Dominique as she speeds off in their car, lugging a

heavy suitcase after him, calling her name. This is after she has coldly and

brazenly told him publically that she doesn’t love him anymore. Here he is having his only credit card cut

into pieces by the bank (her money it seems); and freezing to death sitting on

his suitcase to see how his life will unfold; being shown as an abject failure

again by failing another consummation test with his wife, and being threatened

with arson; playing his comb as a musical instrument as a busker on the Metro

and being told his ‘fly’ is open. It is here, at the Metro, however, that Karol

meets Mikolaj, a fellow Pole from Warsaw, whose friendship will give him a

spark and change his life forever. Before this, however, Kieslowski’s anti-hero

makes a triumphant escape on a flight to Warsaw in a suitcase, only to be a

victim of corrupt baggage handlers who, judging by the weight of the suitcase,

think they have discovered gold. We are shown another scene in which Karol is

lugging his suitcase in the freezing cold, weary, beaten and bloodied, this

time to his former hairdressing salon shop he co-owned with Dominique before

things turned sour. The little shop is amusingly lit up with ‘KAROL’ on a red

neon sign.

Perhaps the most enjoyable scene from the entire film is the

shock on Dominique’s face as she returns to her Parisian flat after the funeral,

to find Karol, shirtless, in her bed. They make passionate love for the first

time and suddenly it seems a cloud has lifted over the fickle Dominique and she

is in love with him. It’s all too late for her. The police arrive and arrest

her for complicit involvement in Karol’s ‘death.’ The film ends with Karol

seeing Dominique through the bars of her prison. She seems, in her sign

language, to be suggesting future plans for being together. He stands there,

weeping, perhaps wondering if it can ever be.

It is difficult to have a colour like white, thematically,

to dominate a film, unlike the tones of red and blue that are so striking in

the other films. Kieslowski, however, finds ways. He creates a snowy landscape

in various parts of the film, especially scenes set in his home city of Warsaw.

As in ‘Dekalog’, his intimate feel for Poland is evident in the way he makes

his film, however it is always a totally unsentimental approach. Kieslowski

also uses a dominance of white in a montage that is repeated throughout. It is

a view of Karol and Dominique’s wedding day. She is beautiful in her white

dress and the background sky is of a cold, milky white. There is also a lovely

scene in the pure white snow in which Karol and Mikolaj are celebrating their

unusual friendship by rolling around on the ground, again under a white winter

sky.

‘Three Colours White’ is probably not as dense as ‘Blue’ but

its exploration of friendship and loyalty on the one hand, and mistrust and

vengeance on the other, make it intriguing. Filming parts of ‘Blue’ at the same

time as filming ‘White’, and even editing ‘Red’ at the same time, and

maintaining ridiculous brief sleeping patterns over a long period of time, is

no mean feat. Juliette Binoche even wanders onto the ‘White’ film set at the

start of the film as if to suggest she is looking everywhere for her director in

order to cut another scene- for the film that she stars in.

No comments:

Post a Comment