EVERYBODY

knows that Sylvia Plath’s father died when she was very young- about eight or

nine, I think. It had an absolutely profound effect on her writing and the way

she viewed the world, as well her relationships and the way she lived her life.

The death, as unnecessary as it seemed, was a cruel blow to an otherwise happy,

yet sometimes intense, precocious child. It is inextricably linked, it seems,

to her many suicide attempts, the earliest it seems when she was finishing high

school and taking medication for depression. This whole thing, dealt with in

her only published novel, ‘The Bell Jar’, makes fascinating reading. And lately

I have come across a very short story called ‘Among the Bumblebees’ which also

deals with the subject of the loss of her father. It was a topic that not only

preoccupied her, but also haunted her, and this early story, written only when

she was about nineteen or twenty, makes compelling reading.

‘Among

the Bumblebees’ starts with an image of her father ‘tossing her up (lovingly)

into the air’ and then ‘holding her in a

huge bear hug.’ The speaker, as Plath as a young girl, is Alice Denway. The reliance

on, and sheer love, of her father is palpable throughout. There are countless

images throughout the beginning of the story of (Mr Plath) as a strong,

reliable and fiercely protective father. (One can’t help wonder if the strong,

sturdy and hulking Ted Hughes whom she later married might not have been a

father replacement, perhaps like Joe DiMaggio might have been temporarily for

Marilyn Monroe).

Alice’s

father is said to be a ‘giant of a man.’ Alice worships him because ‘he was so

powerful.’ He always knew best and ‘never gave mistaken judgement.’ You can

clearly see well ahead of time what poor little Alice Denway will be facing

when such a colossal figure is to all too soon collapse around her.

The

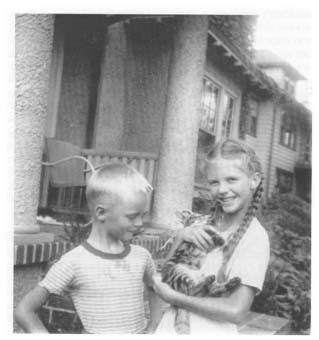

connection between Alice and her father- as opposed to her father and younger

brother Warren (no change in name from real life here)- is made clear. Alice is

simply ‘her father’s pet.’ After she has surreptitiously kicked her little

brother under the table, her father will ‘tweak at her pigtail’ and ask “who’s

my girl?”

The

level of indiscriminate worship is increased even further a little later when

Alice observes her father at work in his study (the scholarly Otto Plath was a

professor and wrote influential books and articles on bees and other insects). Little

Alice imagines her father lecturing students at work ‘like a king, high on a

throne’ with a ‘thundering voice.’ I can imagine Hughes using a thundering

voice, in his case a thick Yorkshire thunder.

And

then, in an image that is very Plath-like, created at such an early stage of

her writing career, she imagines the little red correction marks on her father’s

students’ papers as ‘the color of the blood that oozed out in a thin line the

day she cut her finger with the bread knife.’ One can’t help but think of the

late poem ‘Cut’, written about 1962, which begins (from memory), ‘What a

thrill! My thumb instead of an onion/ The top quite gone/ Except for a sort of

a hinge...’ It is the thrill of the ‘ooze’ in the case of the Alice story that

stays in your memory.

Later

in the story Alice goes swimming with her father. Plath grew up in near Boston,

quite close to the sea, and loved the water her whole life, always lamenting

the crappy English beaches, and often reminiscing, in exile, of the apparently

glorious American ones (Hughes writes of this, memorably, in ‘Birthday Letters’).

During

incredible storms as ‘swollen purple and black clouds’ break open with ‘blinding

flashes of light’, Alice’s father places his ‘strong arms around her’, enabling

her to ‘face the doomsday of the world in perfect safety.’ I am reminded of

another Hughes poem here, called ‘Wind’ from his first book of poems. In this

poem Plath and Hughes can ‘feel the roots of the house move’ and hear ‘the

stones cry out from under the horizon.’ The setting is England this time, but

the idea is the same, even though the male, as fierce protector, is not quite

as well spelt out.

Just

before the crisis which tragically concludes the story, Alice’s father takes

her out to the garden to show her how to catch bumblebees. His extraordinary affinity

with bees seems to parallel the affinity that the Aboriginal writer, Roberta

Sykes, has with snakes. He can stifle an angry buzzing bumblebee in his fist

and then let it go without any hint of being stung. Plath’s lifelong

fascination of bees, inherited obviously from her father, can be seen in a poem

like ‘The Arrival of the Bee Box’, ‘black on black, clambering.’

Then,

suddenly, Alice’s father can only talk in whispers, and the sunlight is too

bright for his eyes. Soon he is very vulnerable, reliant on a ‘plump, silly

doctor’ and his big silver needles. Moreover, his face is the ‘sallow color of

candle wax’ and his flesh is ‘lean and taut about his mouth.’

It

is, undoubtedly like it was in real life, a terribly sad and tragic ending. Bewildered

little Alice stands beside the bed ‘clenching and unclenching her thin hands by

her side’, like a figure in an Edvard Munch painting. She places her head on

her father’s chest as the pulsing of his heart is becoming weaker. The story

concludes with this final sentence:

‘She

did not know then that in all the rest of her life there would be no one to

walk with her, like him, proud and arrogant among the bumblebees.’

Ted

Hughes, who came into her life just four or five years later, may have been,

for a short while, this proud and strong, and imposing, reassuring man, a replacement

figure for her father. But that’s another topic, for another day.