I AM immediately drawn to the name

‘Sokurov’ as I glance over the Melbourne International Film Festival guide in

The Age. It all began at an earlier MIFF occasion- ‘Mother and Son’- going by,

admittedly, a heartfelt recommendation by Nick Cave that was originally

published in ‘The Independent on Sunday’:

Such a simple story of a love a son has for his dying mother. He carries her across stunning landscapes that are filmed with some sort of a distorted – known as anamorphic- lens, inspired by the craftsmanship of Caspar David Friedrich. She is lovingly cradled in his arms like the Pieta, and their image appears at the bottom of the screen, at the bottom of a path that reaches upwards along a kind of valley. It takes some time for the distant figures to reach the top of the screen, hence the top of the mountain. It reminds me of Van Gogh’s appreciation of the Christina Rossetti poem:

‘Does the road go uphill all the

way?’

‘Yes, to the very end.’

‘And does the journey take all day?’

‘From morn to night, my friend.’

Thankfully, Sokurov has all the

patience in the world as we celebrate the moving and beautiful portrait of this

son’s love for his mother. There is very little need for dialogue. Dialogue

would spoil the mood. There are insects, however, and the final inevitable release.

The emotions for the mother are palpable. It is no less tense, but far less complex,

than Paul Morel’s love for Gertrude Morel in Lawrence’s ‘Sons and Lovers.’ Like

Gertrude Morel, this Russian man’s mother dies too, but much more quietly and

peacefully, accepting the inevitability of death. Her son has taken his mother

on her final journey, so there must be a sense of relief for him, too.

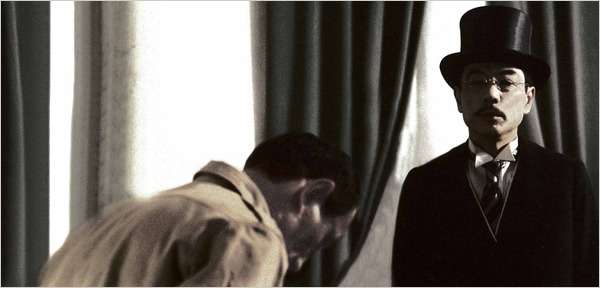

Another MIFF brought us “The Sun’,

about Emperor Hirohito, and the enormous sense of expectation on his shoulders

as Japan’s role in the Second World War becomes increasingly complex and the

war is ending. Hirohito is in a bunker underneath Tokyo. He is fascinated with

marine life and in an extraordinary sequence marvels over a specimen crab.

Equally interesting is his vision of flying fish as airplanes in the sky. It is a very personal piece which examines

Hirohito’s conscience and portrays him as a man who, although at odds

temperamentally with General Macarthur, also in the film, is able to share

dinner and a cigar with him. Hirohito seems timid and child-like, against the

brash American. The American press corps take delight in photographing this

strange, elusive man, which is the funniest moment in the film.

I saw ‘Russian Ark’ at the old

Lumiere cinema in Exhibition Street. A stunning technical achievement, the

camera and the film’s narrators wander through a multitude of rooms inside the

Winter Place, recreating a tapestry of historical events,

all done without any digital editing, in a single sequence. The scene in which

the ghostly figure of the eccentric narrator pauses in front of Rembrandt’s

‘Return of the Prodigal Son’ is a personal favourite. Each room seems to

represent a different historical period, including the time of Peter the Great,

Catherine the Great and the frightening world of Josef Stalin. The location is

beautiful, as are the costumes and paintings. A long sequence of an orchestra

being filmed is slow and seductive, and the large number of inhabitants inside

the Winter Palace, drift out the exit and into the cold air during the closure

of the film.

‘Father and Son’ was played as a one

off at the Nova in Carlton, as part of a Russian Film Festival called, I think,

‘Russian Resurrection.’ The beauty and

honesty and tenderness of a parent and a sibling is quite different here. I

would love to see the film again. I remember a lot of shots on a rooftop

somewhere in Russia, and some stained glass. Like some of his other films,

there isn’t a lot of action. It is mostly meditative. The experience was almost

as equally moving as the tenderness in ‘Mother and Son.’ This time it is like

the touch between father and son in Rembrandt’s ‘The Return of the Prodigal

Son’, except there is a homo-erotic element which I find fascinating. Their

embraces are vigorous and warm and sometimes vaguely sexual.

‘Which takes me to ‘Faust’, which is

based on Goethe’s version, not the Marlowe that I taught at Newent Community

College in Gloucestershire, which is the one I am familiar with. The film went

for over two hours, but it went by very quickly, and tired as I was, I

concentrated on every frame, marvelling at the lighting, the depiction of a

previous time, the ancient villages and rugged landscapes. Faust is

impoverished and unfulfilled and desperate to know the secrets of the soul. He

meets a bizarre Mephistopholean figure, who has a body that is more bestial

than human, with a penis attached from behind rather than at front. Faust makes

his pact, written in his blood, and finds himself unwittingly wearing armour in

the loneliest and most desolate landscape imaginable. This, it seems, is his

Hell- there is no way out and no food or water, not exactly the gates of Hell

opening, as in the Marlowe, but devastating for him nevertheless. I was hoping to see that horrific,

doomed, fiery opening. Faust gets his

woman, the Gretchen, in this film called Margarete. She is pale and innocent

looking, porcelain and quite beautiful, and rural looking. Faust is obviously

desperate for his moment in time with her. When it comes it is surprisingly

understated, rather than being lustful or overtly sexual. Faust does pore over

her naked body but it is sensitively done. Sokurov uses the most intense

close-ups I have ever seen, and her pale face and reddish hair lights up the screen

in this incredible yellow glow. All else is dark. The heads of other members of

the audience are lit up as well. Sokurov revisits the anamorphic lens,

reminiscent of ‘Mother and Son’ again, but this time inconsistently, as if he

wants to try it for a certain effect in some shots only. I read somewhere that

the painterly influence is someone other than Casper David Friedrich this time-

someone I don’t know called David Teniers, a Flemish painter, and a landscape

painter from the same period known as Herri met de Bles. It is the latter that

is the more obvious- I have looked at

these pictures and I can see the striking resemblance.

The influence of a painter on a

director and cinematographer is a fantastic thing. Ingmar Bergman admired

Edvard Munch. I might be wrong, but I thought I could see Munch’s influence

when I saw Bergman’s ‘Cries and Whispers.’ It is the stilted figures, the

sisters, like in the sad, raw Munch pictures that show his grieving family.

The vision of Hell in Sokurov’s ‘Faust’ reminds me a lot of the vision Shakespeare created for the musing Claudio, facing execution, in ‘Measure For Measure:

‘‘…to bathe in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling regions of thick-ribbed ice;

To be imprisoned in the viewless winds,

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendant world.’